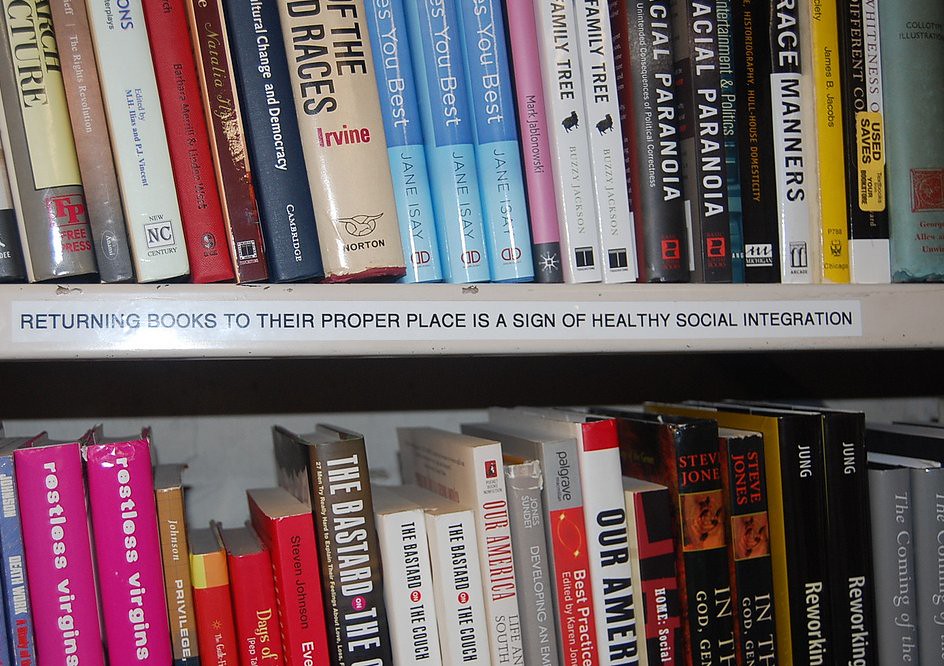

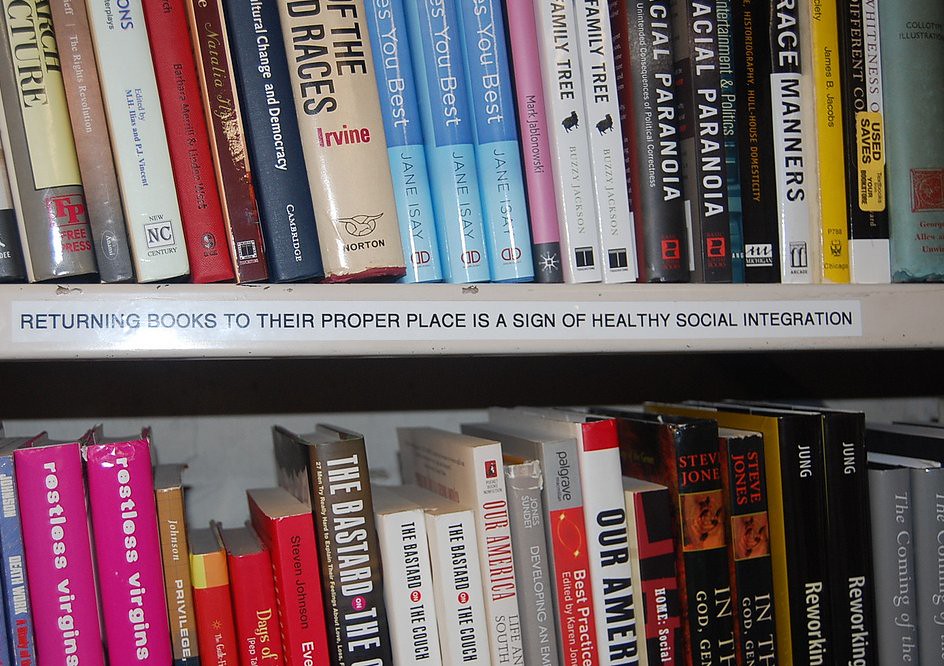

Graffiti/Signs/Art found in Brooklyn, Queens, Pulaski bridge.

Story about a Brooklyn neighborhood I wandered into.

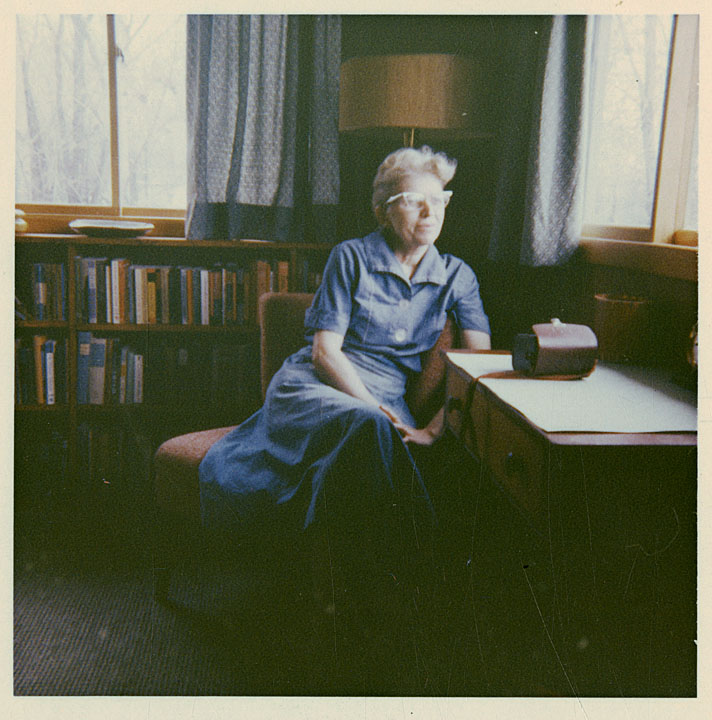

I am a child

and I'm not ready.

.

Therewhere i put my hand.

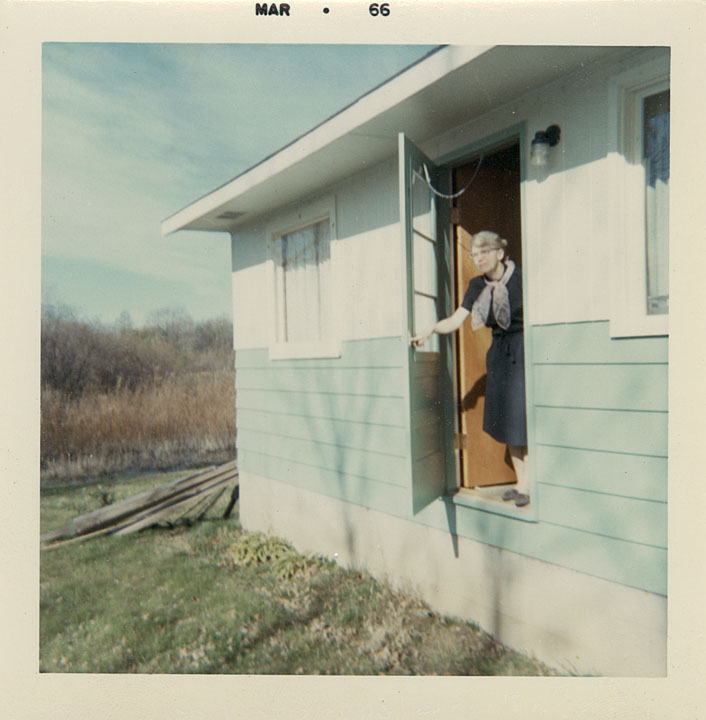

Therewhere I close the door behind me.

Therewhere I unpack my bag.

Therewhere place incites me, chides me, invites me.

Absence Where As

. “If I were just careless and began to have the conversations with myself

if I were a blank page of time

a page of time

that everyone around was folding

so everyone all around just kept folding

parts of me all around up

downs and ups and ups and downs

soft little rips

of visions of morning

WHICH MORNING?

ALL THE ENDLESS MORNINGS AND

ALL THE ENDLESS VISIONS OF THEM ALL

IN

C

utting delirium out

love is not even

little bits of shredded papers

WHO SAYS?

SAID IT SO.

in any way and sleeping through that or the invitations to,

all strange men and woman having conversations

and having conversations

all kinds of conversations and all of them kind of

all of the conversations beginning to be had all

at once in swift ecstatic rotation

spinning and spinning and spinning

feet

flickering off feet flickering the fuck

until sinking to the knees.

.

O Palhaço

Gostava só de lixeiros crianças e árvores

Arras trava na rua por uma corda uma estrela suja.

Vinha pingando oceano!

Todo estragado de azul.

Gullivera

La mujer más alta de la ciudad es seria

y muestra una sonrisa perversa a deshoras

cuando ofrécete un bombón que otro regaló

cuando gravita las cosas al rededor

y dice ‘liliput yourself in your little place’

No sabe la mujer más alta de la ciudad

que la altitud puede ser un peligro

y que tienes ardiles para coger seres así

¿pero para que tú quieres capturarla

si puedes tenerla sin suelo solo aire?

.

Yesterday I smoked the placid lake

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . s a i l bo ats cr as hing

. a ll their little swarmings

threw them more tomorrow

¡Oh!

¡You!

/ desperate delirium gushing / / / / / / / / / / / /

Julia Kristeva quotes Mayakovsky on his experience of rhythmic rapture:

""""""

'"

''"

'''""""

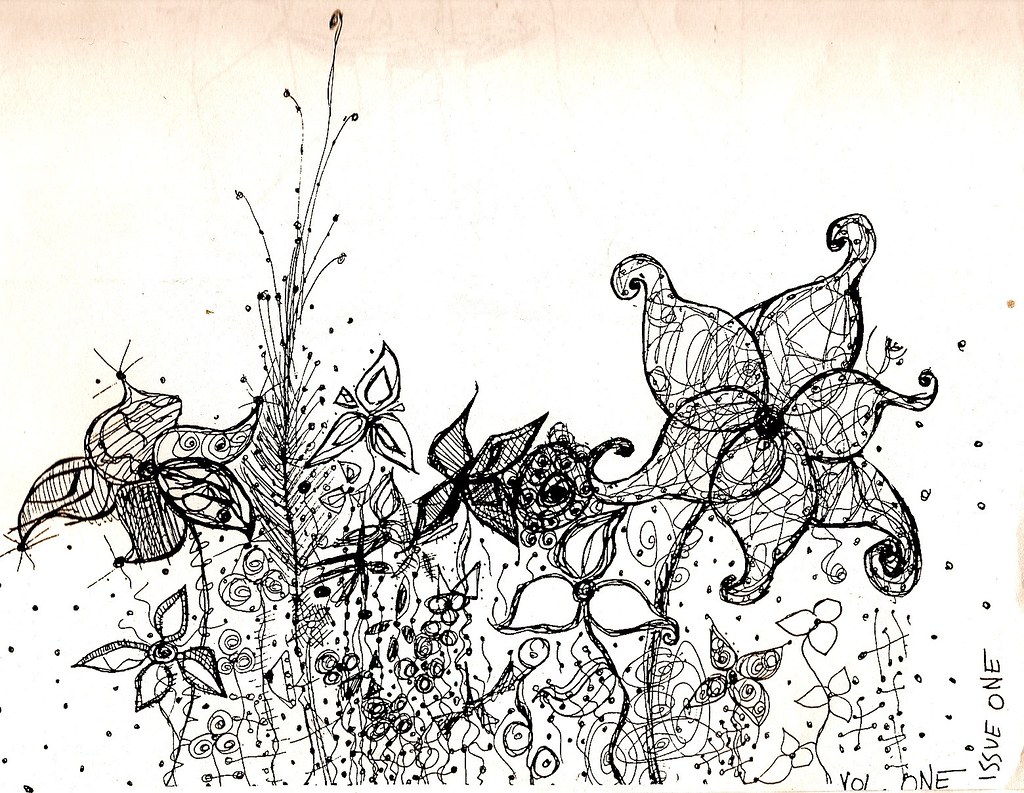

“Rhythm: “I walk along wordlessly interrupt

trimmed poetic work

. . siren raining . .

sun

“there is tornado”

Half way through the garden

harder

I pulled some of the broken ones one after the other

desire

the dangers of living

o

wanting/looking

.

Nameless for Millennia

the Venus of Willendorf was figurative

first and foremost,

a figure of the ripe fat flesh folds:

On the first night, he told her,

“You smell like a cookie.”

Her embouchure pushes through and

“How I want to bite you.”

See the sand colored dunes that drift and shift

See the accumulation

and the rondure of the hills,

soft curvature,

totality of rotation that comes under the pressure of a flat palm pushing down.

I see the moon

and its tenderness has tilted me.

I see the moon and its face turning towards me,

turning off to infinity,

turns its face to face me

turns away to infinity.

Funnels her river there, the current leaks tide

her nipples peaking from the water's bed

dip between the rustling grasses.

A soft hand parts where the mud feels cold

slits the silt open like an envelope,

wet folds with tongue

are pressed firmly to send her off and away.

Corporeal undulations echo over eternity.

However,

the thread of her corn rowed head

is a hand basket afloat in oblivion.

Even at the party, nameless, navel gazing,

he asked her, “so what is it with the constant self-reflexivity thing?”

Her gaze focused on the fat lady's thighs.

He called her Venus as if she'd been missing for millennia.

.

— era um mundo de se comer com os dentes, um mundo de volumosas dálias e tulipas. Os troncos eram percorridos por parasitas folhudas, o abraço era macio, colado. Como a repulsa que precedesse uma entrega — era fascinante, a mulher tinha nojo, e era fascinante.

-Clarice Lispector

Clarice was tiny. She stood only two or three feet tall. She had little golden curls that spilled in tendrils around her face and her face was the face of a cherub, plump and rosy. She did appear so that everyone always had the same thing to say when seeing her for the first time, “oh. You are sweet,” and they truly believed and they were surprised when she spoke: “is that your computer?” her sharp, child’s finger pointing at the woman in the bank who blinked in a way that made her eyelids widen and her eyeballs switch to the other side of her head.

Clarice was tiny because at that point she had only been in the world for a few years. Clarice’s parents took her to the beach. They took Clarice to the beach all the time. The water was a dull turquoise. The red tides cluttered the white sand with broken shells and washed up stars. They dressed her in a blue suit with pink and orange ruffles that floated up around her fat cherub thighs when she sat in the thick, salty water. She was thirsty. She was a jellyfish caught in a hot little tide pool left at noon, abandoned by the sea momentarily until it came to lap her back up again, to rock her in the waves with all of the other fishes instead of drying out alone underneath the sun. She wanted so badly to drift about in that ocean.